A few years ago, when I was just starting my adventure with serious

programming in the Java world, I learned the basics of its largest and

most important framework - Spring. I read Spring in Action, signed up

for a course, and - like every novice (and not only) user - made Google

and StackOverflow searches red. Spring itself is very extensive so

after learning the basics (bean container) I got to know its other

components - SpringMVC, SpringSecurity, SpringData, etc. I remember how

I spent my nights getting to know Spring's secret knowledge and

implementing it in quick exercises. It was not only a pleasure but also

a requirement of the job market - in Java's backend world Spring

is almost everywhere.

As you know, Spring was created as a light, pleasant alternative to EJB (or the whole JEE) which at that time was such a monster that people welcomed Spring with relief and open arms. Although JEE was a semi-official standard I can count projects I have heard about that used it on one hand (at least on the Polish IT market). Albeit JEE has become as convenient as Spring over time - my engineering thesis' project is an example - Spring rules programmers' minds. Have you heard about other serious and well-known Java backend IoC solutions?

A few years ago it seemed to me that Spring is a great framework, without which we are actually bound to use JEE Jakarta or some other niche solutions - how else make a serious application in Java? How to make serious DI? No kidding - you can't do it without Spring… Right?

Hey - did I just write that one of the most popular programming languages in the world is practically dependent? Why does it require something more? And I do not mean additional libraries that provide specific additional functions but the core of the application, the frame-work itself. Why can't we programming without Spring? Shouldn't a programming language with its standard library be sufficient scaffolds for an application? I guess so! So why it isn't'?

This question has bothered me for several years, along with the growing irritation for using Spring. I felt more and more clearly that something is wrong with both this framework and the whole approach to backend application architecture. The longer I programmed, the more I became convinced with it. But what exactly do I not like?

Well, exactly I do not like:

This is a trait not only of Spring or Jakarta, but actually of the paradigm of these solutions. A few years ago I noticed that from the programmer's point of view such a program looks like a set of unlinked elements. Do you notice it too? There is a bean and another one by it. A whole lot of beans. One bean refer to another - or more precisely to a dependency with another bean's type. Although the class of the second bean is right next to it, the programmer don't see its injection. He don't connect it, but the framework, and thus application without this framework is a set of unlinked beans - like a demo. I have to believe that it will be well combined. I cannot see this connection while writing and I am not really sure that a bean will actually be injected. Many times it turned out that it was not - it was enough that I forgot to add an annotation or make a JavaConfig. It is true that a good IDE suggests that something is missing - the problem is that prompting often do not work well. The norm is that the IDE highlights the fields in the class in red to indicate that it does not see this dependencies as Spring's beans - and is almost always wrong because it works. Almost - I can never be sure and injecting the collection I am left with pure faith that it will works.

The biggest problem, however, is with the Spring's own beans. Which

configuration and which settings are actually loaded? I am never 100%

sure what is going on and what these dozens of propertises are actually

for. Can I remove any of them? Will something not work then? I need to

check. Or maybe it's better not to touch it to be sure? Eh...

And have you noticed how testing such a code looks like in practice?

To test such a class, I have to feed it with dependencies. In the case

of a unit test, it often ends in a total mockosis. After all, It's

insane to manually create the entire dependency tree for one test,

right? Mocks will allow me to test a given class by checking exactly

how it used its dependencies and how it reacted to various data from

them - and that's good - but on the other hand, such a tests will be

out of touch with reality. Test cases may have little to do with what

this class actually does. Even if I want to mock some dependencies, I

usually mock most or all of them. The solution to this problem is a

test with the application context. But such tests are

run quite rarely. Why? Because they're slow. And they are slow because

providing context takes a long time. But more on that later.

Of course, I do not mean the criticism of inversion of control (IoC)

- what is in my opinion absolutely right - but about this particular

solution. The beans should get their dependencies from the outside.

However, I dream of a DI that will not hide it under such a large veil

of uncertainty. One where I can easily see it and verify it because it

won't be hidden deep in the Behemoth's bowels. In other words - simple,

readable, easily and quickly verifiable, obvious, statically typed and

validated during compilation.

And does DI need to be provided by an additional framework? In my

opinion, this is such an important, inherent and fundamental issue that

it shouldn't be like that!

Have you ever looked into Spring's insides? Without fear of my

savings, I may buy a beer to each of my friends who know them well. But

should we get to know them? Shouldn't it just be working? In my opinion

it should! So why so many times in job interviews have I heard

questions about the implementation details of this Behemoth? Well,

because the longer you use it, the more you know that it is not that

easy.

Spring is very complicated and as it is the core of many

applications, it transfers this complexity into them. For simple

applications it is not so visible, but remember the software resembles

a garden and grows very easily. In almost every spring application that I

worked on, I saw some tricks, oversized configurations and non-standard

approaches. Probably the most twisted solutions are in SpringSecurity -

the element that should be the most obvious and trustworthy. And in the

days before SpringBoot (not so old after all) it was even worse. Let's

add deep reflection and breaking the code with it to get spaghetti

after which you can get severe indigestion.

Or maybe you know something like this:

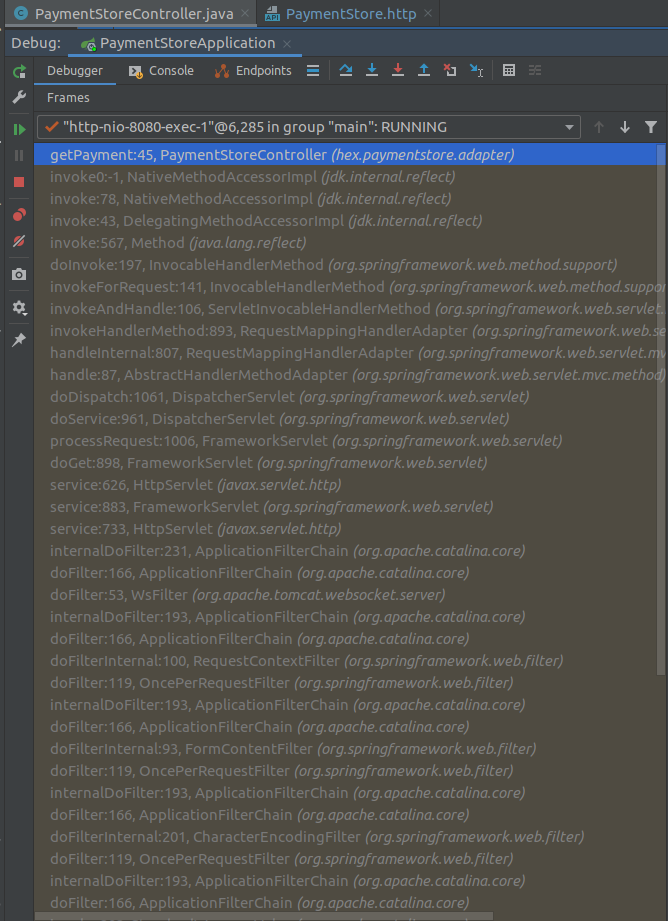

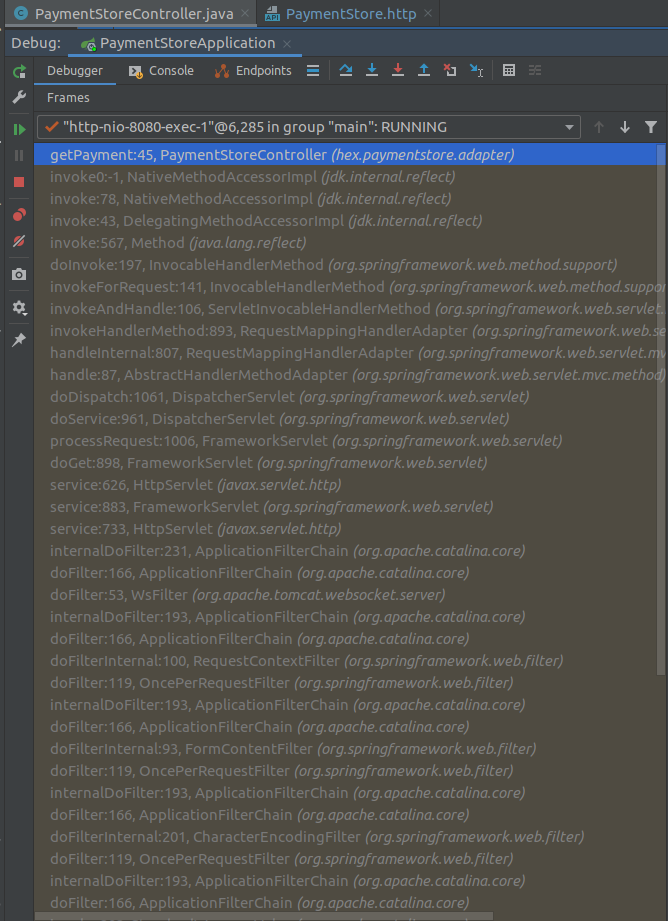

This is a snapshot of the stack in the controller of a very

simple

application. And yes - this is truncated as you can see from the

scroll

bar. Don't You think there is too much of it? If it only concerned

server calls, but I see something like this every time I watch the

communication of beans. I can see it in the exception logs. I can see

it everywhere. Is it normal?

Keep It Simple, Stupid!

There is also a problem of poor performance. The application from the example above is extremely simple. Actually, it is a demo written for the recruitment process for a certain company (and yes - they hired me :)). It is written in the pretty fresh SpringBoot and it start up on my laptop (i7-7700HQ) in about 2 seconds. Not bad, but such an application should start up few times faster. Real Spring business applications sometimes get up so long that you can even make a cup of tea in the meantime. Do we live in the seventies to be so?

Another problem - about which I wrote above - is that integration tests take so long that I know people who do not run them during implementation. Who would want to waste so much time? :) And at the end it turns out that half of the new feature needs to be rewrited.

It is also worth to realize how absurd runing a Spring application looks like. Before SpringBoot, it looked like this: the Spring application is deployed on a servlet container where, with help of deployment descriptor (do you remember such a thing?), The Spring's DispatcherServlet is launched (yes, yes - a remnant of JEE), which raises the context of the application and starts listening. On SpringBoot it is even more interesting because instead of deploying it on an external container, the application runs its own build-in container. How many absurdly unnecessary layers!

In addition to the developer's convenience argument, there is one

more that we will think about when we pay for hosting :)

Do you hear about magic in programming? Something happens automagically - it means somehow and we don't know how. It once impressed me and I wanted to become a magican myself. However, I changed my mind after the myriads of lines of code written. Magic is cool when it works, but when something stops working I want to burn such magicans at the stake. I don't mean, of course, using abstractions, libraries or delegate responsibility. These are the things that engineers should use. However, Spring and similar tools do it wrong. Declarative programming combined with breaking the code with deep reflection and a spring mess, where I am never sure if something will work, makes that instead of programming with pleasure and focusing on business logic, I feel like an engineer meeting a shaman - I don't know if I should look at him with admiration or embarrassment (although with time I look with embarrassment more and more often). I'm just waiting for applications that will be written only as spring yaml configurations.

Do you pine for the days when programmers were programmers and wrote their own applications?

Finally, one more reflection. Do you remember the UNIX philosophy? I know that it is often not used anymore, that there is a lot of good software that is definitely not small and single-purpose and that, as everything in life, you need to find a convenient solution. Spring's philosophy, however, is an inflection. More than a breeze of spring, it already resembles a hailstorm. "Since we already have Spring, let's use SpringXxx - we get it almost for free and it's probably cool, right?" Doesn't it remind you of something?

One ring to rule

them all,

one ring to find them,

One ring to bring them all

and in the darkness bind them.

A few years ago, I started to wonder how you can get around these

problems. I was looking for a sensible alternative that would not

duplicate these drawbacks and at the same time give the convenience of

creating efficient, scalable, testable and expandable applications. I

remember three years ago when I was at Confitura conference, I

saw this

talk about alternatives to Spring. I also remember that it made a

very

poor impression on me - instead of showing some interesting and

sensible alternatives, it confirmed my belief that such alternatives

practically do not exist. However, a few months later I saw Jarosław

Ratajski's speech

which perfectly fit my thoughts and confirmed my

belief that the language itself has everything I need. Unfortunately, I

did not find any specific proposals in this speech, so I tried to write

a very simple DI framework based on a mirocontainer by myself. It

solved many of the problems discussed above, but it was still not a

perfect solution, so I started to wonder how to make a good DI without

any framework. I made a few assumptions. It should be:

About a year and a half ago, I had an idea how to do this. The arrival of the coronavirus plague in 2020 and the related restrictions have given me the time and impetus to try to write some application based on this idea.

At that time, I also met and fell in love with a new language - Kotlin. It is what I need from the language and what Scala should have been from the beginning and never became. Since then, I have been writing privately on JVM only in Kotlin - and trying my hand at Kotlin outside of JVM. This language and its entire ecosystem bring many interesting solutions. It also makes things that would be breakneck and uncomfortable in Java, as comfortable, elegant and simple. It allows me to focus on the merits instead of heroically struggling with things I shouldn't be doing at all. The aforementioned idea for a solution is based on Kotlin and thanks to this language it is possible to meet the assumptions of simplicity and convenience.

The solution I came up with is trivial, but it seems to meet the above assumptions. It is based on Kotlin's objects and a specific design pattern that can be called Lazy Properties Application Context.

You probably know the Singleton design pattern - all programmers

learn it and hardly anyone uses it. This does not mean, however, that

we do not need classes with only one instance, but we get it from the

framework that takes care of their creation. For several years I have

felt that something is wrong here. These instances are often impossible

to create without deep reflection, or they are just plain constructor

classes. In the first case, we become even more dependent on the

framework, and in the second, we completely deviate from the Singleton

pattern. The ideal solution would be if the language itself supports

this pattern and this is exactly what the Kotlin's

objects are. I decided to use them as the basis for the application

beans.

However, we do not always want to refer to a given bean directly, but we need to hide it behind an interface. In the architecture of ports and adapters, the domain should not know the specific implementation of the adapter at all. This is where the application context comes in handy. However, the container-based context is what I just wanted to avoid, so the solution came to my mind - I just need a contextual class where beans will be its fields (in the Kotlin world it is called properties). Singletons can get their dependencies from such a source instead of the constructor. An almost trivial solution. To avoid problems with loading the beans and their sequence, I made them lazy. To that I added a very simple profile implementation and that's it! But talk is cheap. The code looks like this:

open class AppContext(args: Array<String>) {

val properties = lazy { AppProperties(args) }

private val profiles = lazy { listOf(DemoProfile).filter { properties.value.profiles.contains(it.name) } }

private fun <T> from(supplier: (Profile) -> T?): T? = profiles.value.firstNotNullOfOrNull(supplier::invoke)

open val postsRepository = lazy { from(Profile::postsRepository) ?: DatabasePostsRepository }

open val databaseConnection = lazy { DriverManager.getConnection(properties.value.dbURL) }

}

private interface Profile {

val name: String

val postsRepository: PostsRepository? get() = null

}

private object DemoProfile : Profile {

override val name = "demo"

override val postsRepository: PostsRepository = DemoPostsRepository

}

Just a dozen lines of code. Each bean in context is one line of code - the same as @Component annotation or JavaConfig entry. The beans may or may not be profile dependent. Additionally, a separate context can be prepared for the tests:

object TestContext : AppContext(arrayOf()) {

override val databaseConnection = lazy<Connection> { DriverManager.getConnection("jdbc:sqlite::memory:") }

}

Here's what loading beans from context looks like:

object Controller {

private val repository by appContext.postsRepository

And it is validated on compilation time (of course, the IDE easily

prompts everything) and statically typed. It is also subject to the

Kotlin's null safety.

I was also wondering if all beans should be in context, and decided

that I will only give there those that really depend on the runtime

context, are adapters (in the architecture of ports and adapters) and

those that I would like to mock in tests. Everything else can be

directly invoked regular objects.

This solution gives inversion of control without the use of a

container. And what about the functionalities that Spring gives us?

Here I stated that we should apply the UNIX principle. There are a plenty

of solutions on the market for every need and I will deal with their

analysis and comparison on this blog.

Exactly. I was curious how such a solution would fall into practice,

so I decided to combine it with my plan to create this blog and wrote

it as an application based on this idea. It turned out that it works

without any problems and, in my opinion, meets all the assumptions. It

starts up in no time and works flawlessly. As a server I used Ktor -

the most popular server in the Kotlin world. I had some concerns about

it - it is actually a framework. Fortunately, it is limited to serving

and does not affect the overall application; it's well customizable and

has great documentation.

Everything is published on GitHub here.

This

application is very simple and will grow with this blog, which will

become the best test for it.

Please review the code and let me know

what you think :)